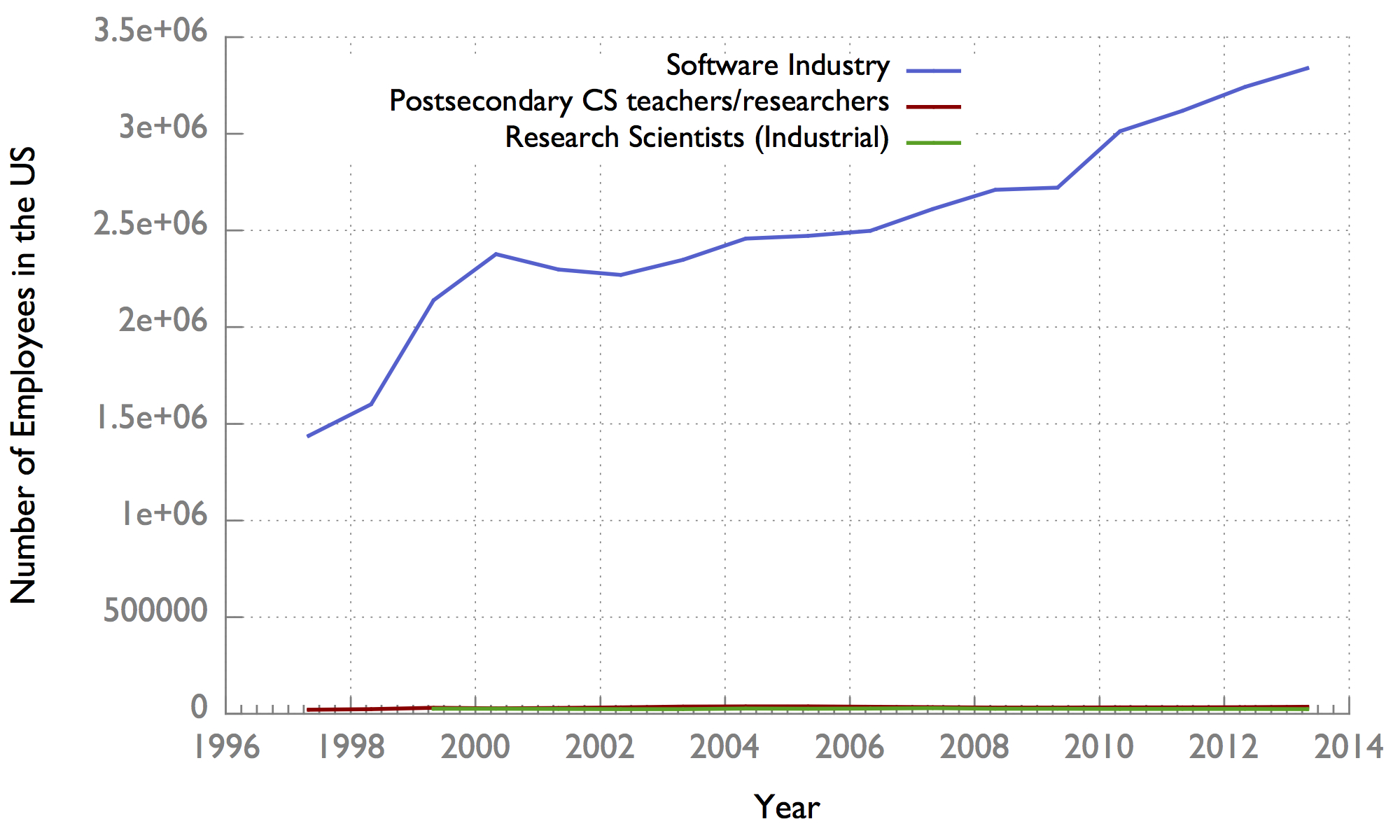

Research on distributed systems is often motivated by some variation of the following:

Developers of distributed systems face notoriously difficult challenges, such as concurrency, asynchrony, and partial failure.

That statement seems convincing enough, but it’s rather abstract. In this post

we’ll gain a concrete understanding of what makes distribution so challenging,

by describing correctness bugs we found in an implementation of the Raft consensus protocol.

Raft is an interesting example because its authors designed it to be

understandable and straightforward to implement. As we’ll see, implementing even the relatively

straightforward Raft spec correctly requires developers to deal with many difficult-to-anticipate

issues.

Fuzz testing setup

To find bugs we’re going to employ fuzz testing. Fuzz tests are nice because

they help us exercise situations that developers don’t anticipate

with unit or integration tests. In a distributed environment,

semi-automated testing techniques such as fuzzing are especially useful, since the number of possible

event orderings a system might encounter grows exponentially with the number

of events (e.g. failures, message deliveries)–far too many cases for developers to reasonably cover with

hand-written tests.

Fuzz testing generally requires two ingredients:

- Assertions to check.

- A specification of what inputs the fuzzer should inject into the system.

Assertions

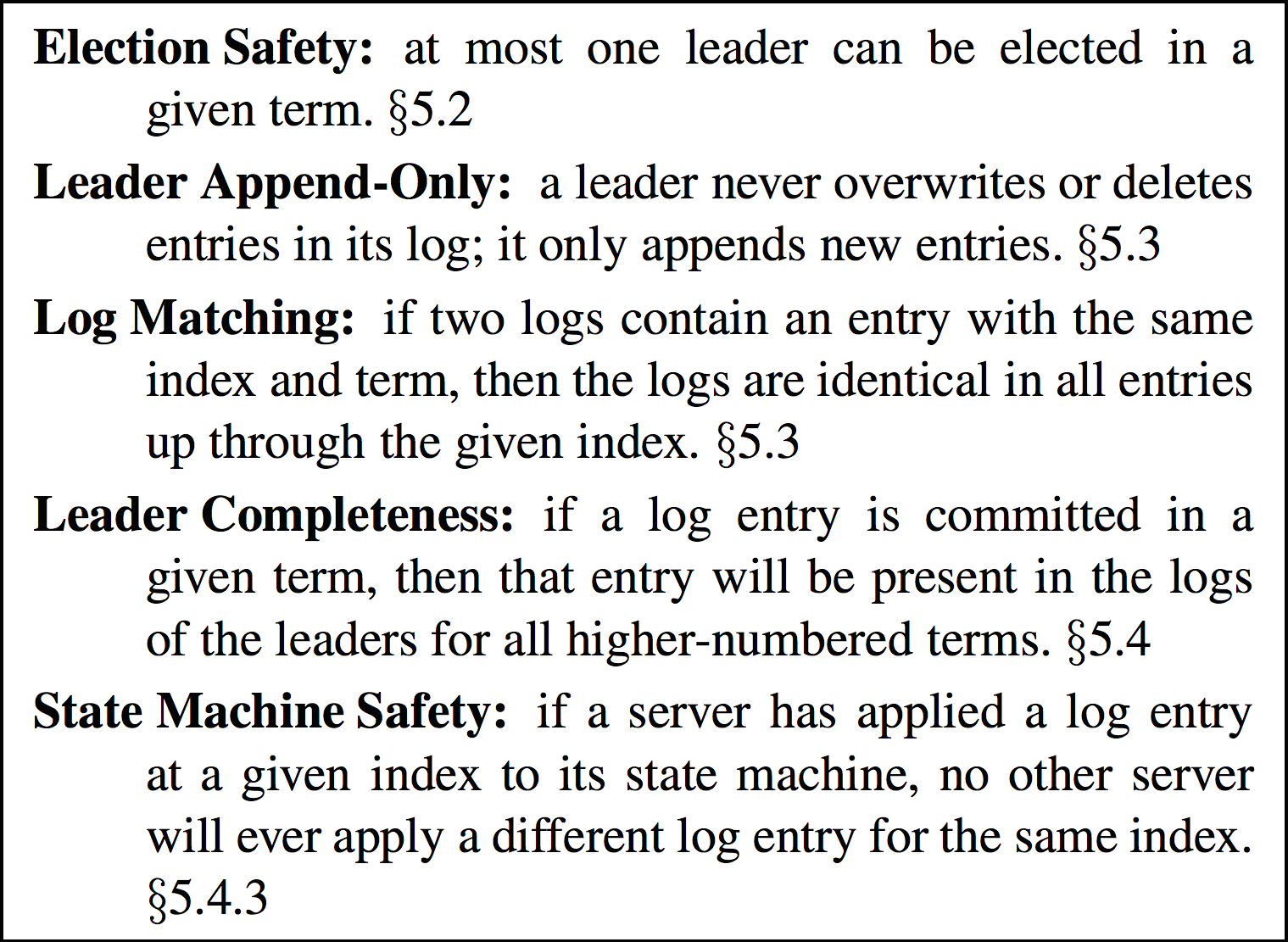

The Raft protocol already has a set of nicely defined safety

conditions, which we’ll use as our assertions.

Figure 3 from the Raft paper (copied left) shows Raft's key invariants.

We use these invariants as our assertions. Each assertion should hold at

any point in Raft's execution.

For good measure, we also add in one additional assertion:

no Raft process should crash due to an uncaught exception.

We'll check these invariants by periodically halting the fuzz test and

inspecting the internal state of each Raft process. If any of the assertions

ever fails, we've found a bug.

The trickier part is specifying what inputs the fuzzer should inject.

Generally speaking, inputs are anything processed by the system, yet created outside the control of

the system. In the case of distributed systems there are a few sources of

inputs:

- The network determines when messages are delivered.

- Hardware may fail, and processes may (re)join the system at random points.

- Processes outside the system (e.g. clients) may send messages

to processes within the system.

To generate the last two types of inputs, we specify a function for creating random external messages (in the case of Raft: client commands)

as well as probabilities for how often each event type (external message sends, failures, recoveries) should be injected.

We gain control over the network by interposing on the distributed system’s RPC layer, using AspectJ. For now, we target a

specific RPC system: Akka. Akka is ideal because it provides

a narrow, general API that operates at a high level abstraction

based around the actor model.

Our interposition essentially allows us to play god: we get to choose exactly when each

RPC message sent by the distributed system is delivered. We can delay, reorder, or drop any message the

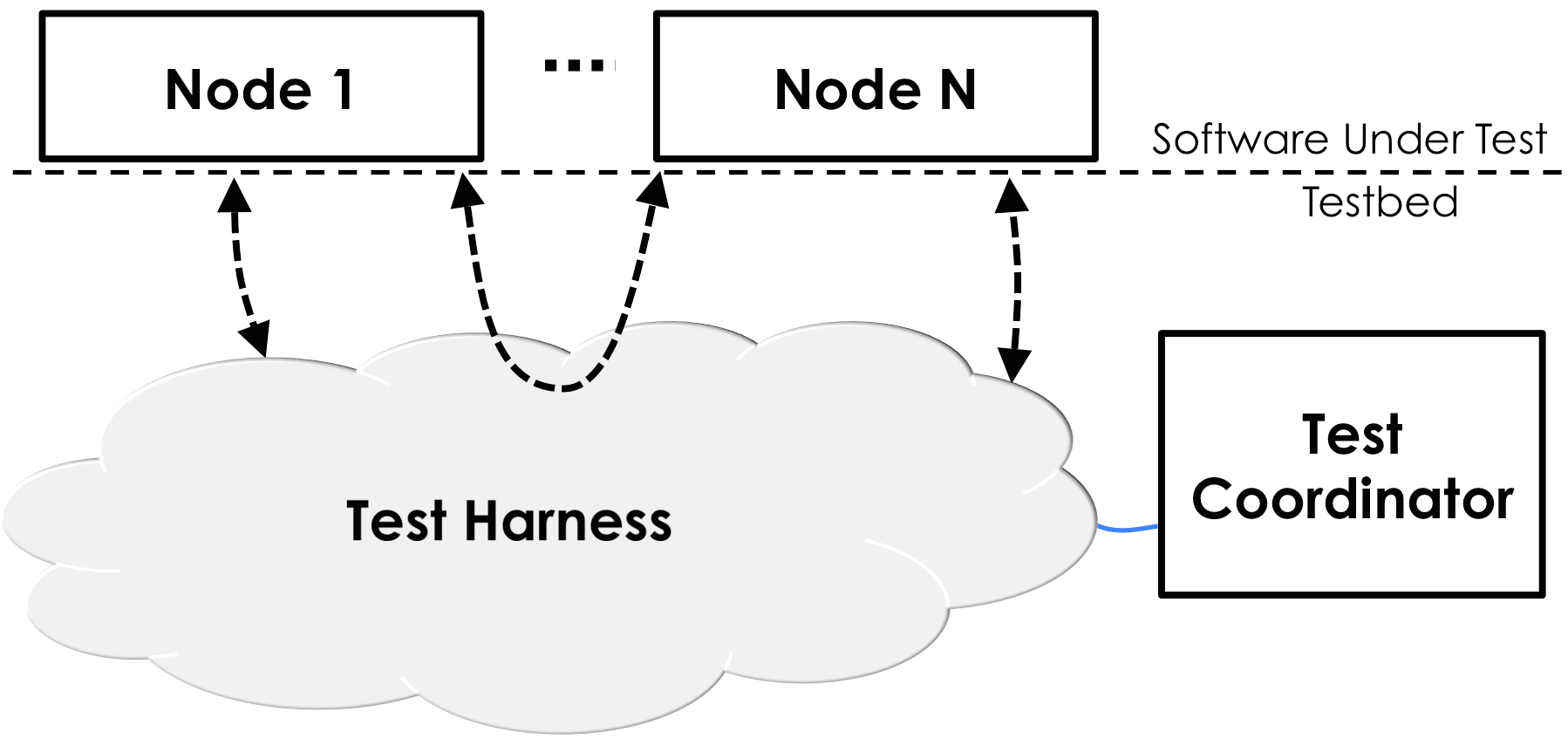

distributed system tries to send. The basic architecture of our test harness

(which we call DEMi) is shown below:

Every time a process sends an RPC message, the Test Harness intercepts it and places

it into a buffer. The Test Coordinator later decides when to deliver that message to the recipient.

In a fully asynchronous network, the Test Coordinator can arbitrarily delay

and reorder messages.

The Test Coordinator also injects external events (external message sends, failures, recoveries)

at random according to the probability weights given by the fuzz test

specification.

Interposing at the RPC layer has a few advantages over interposing at a

lower layer (e.g. the network layer, a la Jepsen).

Most importantly, we get fine-grained control over when each individual

(non-segmented) message is delivered. In contrast, iptables is a much more blunt tool: it only allow the tester

to drop or delay all packets between a given pair of processes [1].

Targeting applications built on Akka gives us one other

advantage: Akka provides a timer API that obviates the need for application

developers to read directly from the system clock. Timers are a crucial part of distributed systems,

since they are used to detect failures. In Akka, timers are modeled

as messages, to be delivered to the process that set the timer at a later

point in the execution. Rather than waiting for the wall-clock time for each

timer to expire, we can deliver it right away, without the application

noticing any difference.

Target implementation: akka-raft

The Raft implementation we target is akka-raft. akka-raft is written by one of the

core Akka developers, Konrad Malawski. akka-raft is fully featured according to

the Raft implementation page; it supports log

replication, membership changes, and log compaction. akka-raft has existing

unit and integration tests, but it has not yet been deployed in production.

UPDATE: Konrad asked me to include a short note, and I’m glad to oblige:

akka-raft is not an officially supported Akka module, but rather just a side project of Konrad’s. The Akka modules themselves are much more rigorously tested before release.

For our fuzz tests we set up a small 4-node cluster (quorum size=3). akka-raft

uses TCP as its default transport protocol, so we

configure DEMi to deliver

pending messages one-at-a-time in a semi-random order that obeys FIFO order

between any pair of processes. We also tell DEMi to inject a given number of client

commands (as external messages placed into the pending message buffer), and

check the Raft invariants at a fixed interval throughout the execution. We do

not yet exercise auxiliary features of akka-raft, such as log compaction or

cluster membership changes.

Bug we found

For all of the bugs we found below, we first minimized the faulty execution

before debugging the root cause [2]. With the minimized execution in hand,

we walked through the sequence of message deliveries in the

minimized execution one at

a time, noting the current state of the process receiving the message. Based on

our knowledge of the way Raft is supposed to work, we found the places in

the execution that deviated from our understanding of correct behavior.

We then examined the akka-raft code to understand why it deviated, and came up

with a fix. We submitted all of our fixes as pull requests.

A few of these root causes had already been pointed out

by Jonathan Schuster through a manual audit of the code, but

none of them had been verified with tests or fixed before we ran our fuzz

tests.

On with the results!

raft-45: Candidates accept duplicate votes from the same election term.

Raft is specified as a state machine with three states: Follower, Candidate,

and Leader. Candidates attempt to get themselves elected as leader by

soliciting a quorum of votes from their peers in a given election term (epoch).

In one of our early fuzz runs, we found a violation of ‘Leader Safety’, i.e. two

processes believed they were leader in the same election term. This is a bad

situation for Raft to be in, since the leaders may overwrite each other’s log

entries, thereby violating the key linearizability guarantee that Raft is supposed to

provide.

The root cause here was that akka-raft’s candidate state did not detect

duplicate votes from the same follower in the same election term.

(A follower might resend votes because it believed that an earlier vote was

dropped by the network). Upon receiving the duplicate vote, the candidate

counts it as a new vote and steps up to leader before it actually

achieved a quorum of votes.

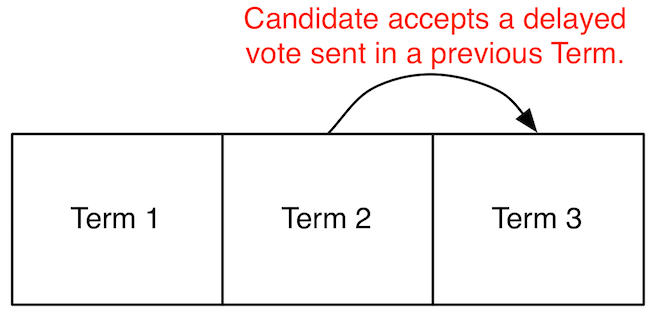

raft-46: Processes neglect to ignore certain votes from previous terms.

After fixing the previous bug, we found another execution where two leaders

were elected in the same term.

In Raft, processes attach an ‘election term’ number to all messages they send.

Receiving processes are supposed to ignore any messages that contain an

election term that is lower than what they believe is the current term.

akka-raft properly ignored lagging term numbers for some, but not all message

types. DEMi delayed the delivery of messages from previous

terms and uncovered a case where a candidate incorrectly accepted a vote message from

a previous election term.

raft-56: Processes forget who they voted for.

akka-raft is written as an FSM. When

making a state transition, FSM processes specify both which state

they want to transition to, and which instance variables they want to keep

once they have transitioned.

All of the state transitions for akka-raft were correct except

one: when a candidate

steps down to follower (e.g., because it receives an AppendEntries message,

indicating that there is another leader in the cluster), it

forgets which process it previously voted for in that term. Now, when another

process requests a vote from it in the same term, it will vote again but this

time for a different process than it previously voted for, allowing

two leaders to be elected.

raft-58a: Pending client commands delivered before initialization occurs.

After ironing out leader election issues, we started finding other issues. In

one of our fuzz runs, we found that a leader process threw an assertion error.

When an akka-raft candidate first makes the state transition to leader, it does not

immediately initialize its state (the nextIndex and matchIndex variables).

It instead sends a message to itself,

and initializes its state when it receives that self-message.

Through fuzz testing, we found that it is possible that the candidate could have pending ClientCommand messages

in its mailbox, placed there before the candidate transitioned to leader

and sent itself the initialization message.

Once in the leader state, the Akka runtime will first deliver the ClientCommand message. Upon processing the ClientCommand

message the leader tries to replicate it to the rest of the cluster, and updates its

nextIndex hashmap.

Next, when the Akka runtime delivers the initialization self-message, it will overwrite the

value of nextIndex. When it reads from nextIndex later, it’s possible for

it to throw an assertion error because the nextIndex values are

inconcistent with the contents of the leader’s log.

raft-58b: Ambiguous log indexing.

In one of our fuzz tests, we found a case where the ‘Log Matching’

invariant was violated, i.e. log entries did not appear in the same order on

all machines.

According to the Raft paper, followers should reject AppendEntries requests from leaders that are

behind, i.e. prevLogIndex and prevLogTerm for the AppendEntries message are

behind what the follower has

in its log. The leader should continue decrementing its nextIndex hashmap

until the followers stop rejecting its AppendEntries attempts.

This should have happened in akka-raft too, except for one hiccup:

akka-raft decided to adopt 0-indexed logs, rather than 1-indexed logs as the

paper suggests. This creates a problem:

the initial value of prevLogIndex is ambiguous:

- followers can’t distinguish between an

AppendEntries for an empty log (prevLogIndex == 0)

- an

AppendEntries for the leader’s 1st command (prevLogIndex == 0), and

- an

AppendEntries for the leader’s 2nd command (prevLogIndex == 1 - 1 == 0).

The last two cases need to be distinguishable.

Otherwise followers won’t be able to reject inconsistent logs. This corner would have

been hard to anticipate; at first glance it seems fine to adopt the convention

that logs should be 0-indexed instead of 1-indexed.

raft-42: Quorum computed incorrectly.

We also found a fuzz test that ended in a violation of the ‘Leader Completeness’ invariant, i.e. a newly elected leader

had a log that was irrecoverably inconsistent with the logs of previous leaders.

Leaders are supposed to

commit log entries to their state machine when they knows that a quorum (N/2+1) of

the processes in the cluster have that entry replicated in their logs.

akka-raft had a bug where it computed the highest replicated log index incorrectly.

First it sorted the values of matchIndex (which denote the highest log entry index

known to be replicated on each peer). But rather than computing the median

(or more specifically, the N/2+1’st) of the sorted entries, it computed the mode of the sorted

entries. This caused the leader to commit entries too early, before a quorum

actually had that entry replicated. In our fuzz test, message delays allowed another leader to become elected, but it did not have all

committed entries in its log due to the previously leader committing too soon.

raft-62: Crash-recovery not yet supported, yet inadvertently triggerable.

Through fuzz testing I found one other case where two leaders became elected in

the same term.

The Raft protocol assumes a crash-recovery failure model – that is, it allows

for the possibility that crashed nodes will rejoin the cluster (with non-volatile state

intact).

The current version of akka-raft does does not write anything to disk

(although the akka-raft developers intend to support persistence soon).

That’s actually fine – it just means that akka-raft currently assumes a crash-stop failure

model, where crashed nodes are never allowed to come back.

The Akka runtime, however, has a default

behavior that doesn’t play nicely

with akka-raft’s crash-stop failure assumption: it automatically restarts any process that throws an exception.

When the process restarts, all its state is reinitialized.

If for any reason, a process throws an exception after it has voted for

another candidate, it will later rejoin the cluster, having forgotten who it had

voted for (since all state is volatile). Similar to raft-56,

this caused two leaders to be elected in our fuzz test.

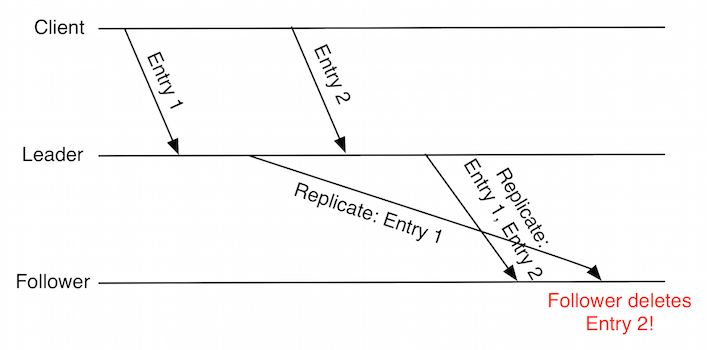

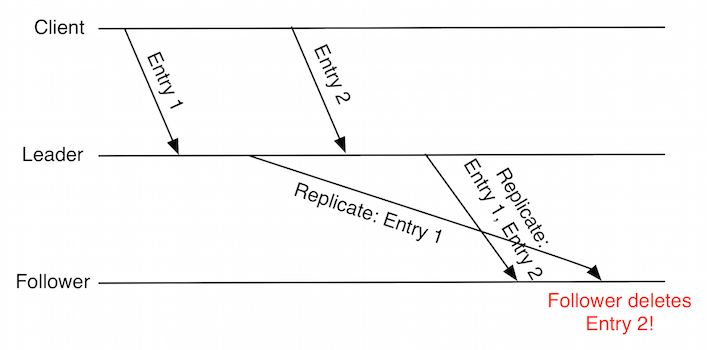

raft-66: Followers unnecessarily overwrite log entries.

The last issue I found is only possible to trigger if the underlying

transport protocol is UDP, since it requires reorderings of messages between

the same source, destination pair. The akka-raft developers say they don’t currently

support UDP, but it’s on their radar.

The invariant violation here was a violation of the ‘Leader Completeness’ safety property, where a leader is

elected that doesn’t have all of the needed log entries.

Leaders replicate uncommitted ClientCommands to the rest of the cluster in batches.

Suppose a follower with an empty log receives an AppendEntries containing

two entries. The follower appends these to its log.

Then the follower subsequently receives an AppendEntries containing only the

first of the previous two entries. (This message was delayed, as shown in the

Lamport Time Diagram). The follower will inadvertently delete the second entry from its log.

This is not just a performance issue: after receiving an ACK from the follower, the leader is under the impression that the

follower has two entries in its log. The leader may have decided to commit both

entries if a quorum was achieved. If another leader becomes elected, it will not necessarily have

both committed entries in its log as it should.

Conclusion

The wide variety of bugs we found gets me really excited about how useful our

fuzzing and minimization tool is turning out to be. The development toolchain for

distributed systems is seriously deficient, and I hope that testing techniques like

this see more widespread adoption in the future.

I left many details of our approach out of this post for brevity’s sake,

particularly a description of my favorite part: how DEMi minimizes the faulty executions

it finds to make them easier to understand. Check

out our paper draft for more details!

[1] RPC layer interposition does come with a drawback: we’re tied to a

particular RPC library. It would be tedious for us to adapt

our interposition to the impressive range of systems Jepsen has been applied

to.

[2] How we perform this minimization is

outside the scope of this blog post. Minimization is, in my opinion, the most

interesting part of what we’re doing here. Check out our

paper draft for more

information!